Odium Fati

I hate this fate. Writing about Clem.

I’ve been thinking a lot about a dream I had about a month ago; in it, Clem was up and about and had this beautiful look of surprise and gratitude in his eyes. “I feel good today,” he said to me. And in the dream, I was flooded with relief, a respite from the relentless sadness that had wrapped every day of my life since he’d told me the bad news. The dream feelings were deep and real, and so intertwined and layered, exactly as awake feelings are. Under the reprieve, pulsing below the moment of happiness was the knowledge that it wouldn’t last. It wasn’t negating or erasing anything, but the threat and the dread could never allow you to forget.

I woke up from that dream shaken at how much I’d felt it, how little solace it gave me and how oddly pointed it was to pierce a simple, basic aspect of life: feeling good. Feeling good is minimal, it’s absence of pain and suffering, it’s being able to feel like yourself, familiar. Feeling good is one of the cruelest thefts of cancer and treatment.

A week after the dream, I was frantically trying to arrange an air ticket change so that I could arrive two days earlier than I was booked to Los Angeles. Two days more time was worth whatever it cost to change. I’ve never been too hung up on money. To me, time is infinitely more valuable. Money spent that saves me time or gives me more time is money well spent. Across the board. The greatest thing money can do is buy time. And I wanted all the time I could have with my best friend.

His doctor, the one I arranged for him to meet at the beginning, who I begged to take a look at his case, and who Clem decided was the right doctor to oversee his care, had determined that treatment was no longer an option and that the next best step was hospice care. I got into LA, climbed into the bed next to him and when he woke up, I told him. It had to be me. I’d been protective and honest, positive and realistic, and a valiant advocate throughout the illness, both away and during my many visits to be there for him.

“Fuck,” he said. “So I’m dying?”

“I think so, but not today,” I said. He went back to sleep.

Things went fast after that. The changes happened on Wednesday, the next Saturday, mid-week, the following weekend. My rehearsals with the Go-Go’s started, 4-5 hours each day, but I spent mornings and evenings, as much as I could, and our little team of Clem support made sure he was looked after. The end was so swift, and unexpected—yes, even with terminal illness, they can tell when it is imminent, and it wasn’t. It happened sooner than expected, but was peaceful, and easy, and the nurse we’d gotten to stay that night told me she was sure he’d waited until I was there, laying next to him like I had so many times.

Last month we watched all the Godfather movies together. The last book he read was “Sonny Boy”—the Al Pacino memoir. That was a few months ago. The last song he listened to was “Perfect Day” by Lou Reed. That was about a week before he died. Cancer took his interest and passion for all the things he’d always loved. It’s hard to have interest in much if you don’t feel good. Cancer did not take his pride. No one deserves to be sick, but Clem monumentally did not deserve it. He refused to be known as a sick man. I honor his privacy by not discussing any further this disease or what he went through. This is about Clem as I knew him.

Clem was spectacular. When I think of him, I think of his life force: the energy, vitality, stamina, and charisma that he embodied as effortlessly as breathing. I think of his joy and passion when he played drums. I think of how devastatingly good looking and elegant he was, without an ounce of self-consciousness or doubt about his appearance ever. I think of his boyish smiles, his ease and confidence in every setting and situation, his conviction and certainty in his own taste and preferences. I think of his devotion to music and his friends.

Things you wouldn’t know unless you knew him, things I’d like you to know: Clem was tolerant and open-minded, which naturally put him on the left side of politics. He paid attention, watched the news, read the paper, voted. He didn’t pretend to know more than he knew, and was curious and interested in listening to anyone he could learn from. He didn’t care for gossip and had little interest in people’s private lives. He never made jokes at other people’s expense and was steadfastly loyal. He treated his friends who were renowned and famous exactly how he treated his friends who were neither.

His interests tended to revolve around music, pop culture, art, rock history, records and recording, movies, books, style and fashion. He loved the music trades and magazines, saving hundreds of them because they had articles he thought were too important to toss. It was a continual surprise how much he knew about films and bands and records, it was always fresh, I never heard him repeat the same information.

He was complicated and simple at the same time. He was generous and frugal at the same time. He was shy and humble in equal parts as he was arrogantly confident about his place in his chosen world. Clem was very resistant to change, he didn’t “pivot,” but was also very adventurous and independent. He spent a lot of time on his own, more than anyone I know. I often worried that he was lonely, but instead of making him depressed, his willingness to be alone seemed to make him stronger.

Whether on the road or at home, he never took his health for granted and worked hard to make sure his strength and stamina to play his best was in peak form. Clem would call me from the treadmill at the gym, usually around the second hour of his run, and not even be out of breath. It was a basic routine for him to spend a couple hours running, an hour on weights, an hour in the sauna, then go home and swim for an hour. One Christmas I gave him a basket full of health supplements, a fortune’s worth of supplies of Sun Chorella and vitamins, and it might have been the best gift I ever came up with.

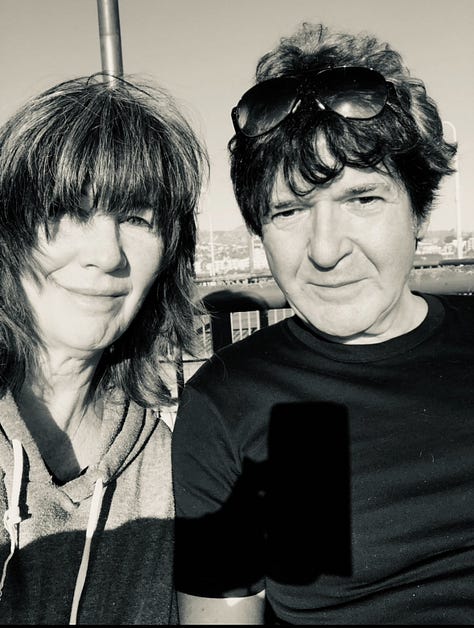

When he wasn’t alone, he absolutely loved showing you the places he’d discovered or knew about. A year ago, last March, shortly after I’d moved to England, we spent a day walking, for hours. 1000s of steps, from Notting Hill to Kensington to Covent Garden to Soho, ducking into the Gore Hotel where the Stones threw their Beggar’s Banquet release party, to the Colony Room Bar where Francis Bacon and a retinue of outsiders and elites debauched and drank through the night, to the spot where Bowie was shot for the Ziggy Stardust album cover. We ended up at Claridges where he got high tea comped for us. He knew places and facts and history in cities all through North America, Australia, and Europe, and was the best guide and exploring partner. He had friends or knew people everywhere. Over the years of our love and friendship, we traveled to Italy, Spain, France, Greece, Mexico and Jamaica together. Each trip is a vividly saturated memory.

I understood him perfectly and accepted him unconditionally. I knew the source of his discipline and need for control, and why the various encountered life traumas that challenged his well being could sometimes elicit a fit of anger. I cherished his laughter, his smiles, and his unwavering support. I knew without reservation that he would always be there for me.

He was terrified to tell me why, after all, he wouldn’t be able to be there for me always. He knew how lost I would feel. I don’t think he knew how fiercely I would insist on being there for him, flying back and forth across an ocean and continent to do my best to ease and soften the tragic fate that had randomly chosen him.

I think I fell in love with Clem the very first time I saw him play the drums. It might have been the Mike Douglas show, circa 1978. He played a red sparkly kit, wore a black suit, white shirt, black tie, that jet black mop top of hair framing this angelically handsome baby face. I couldn’t wait for the camera to wander off Debbie for a bit and find him. Notably, the camera found him more than anyone else in the band. I was smitten, like countless other girls and boys, over Clem Burke. By the end of 1984, we were in love, and stayed that way, although the shape of the love would change from romantic to a deep familial bond and friendship. We were each other’s brother and sister, two only children who longed for more family, more connection.

It was Clem that made me start really paying attention to the drummer in a band. As a rocknroll fan, I certainly knew who the drummer was in my favorite bands; Keith Moon, Bonham, Charlie, Ringo—but I don’t think I ever really focused on their playing until Clem’s playing showed me what the drums did for a song, for a vibe, for a band. Maybe another drummer could talk better about his particular style and technique, but I know enough to say some things. There’s talent, and there’s sensational, singular combinations of more than talent. I know the primary reason he commanded attention is because he was having fun, the best, most consummate kind of fun. His head bopping and shaking, completely absorbed in the music, completely committed to giving the moment; the other musicians, the audience, the singer, the song—everything he’s got to give. He could play thunderously and tastefully over the top, while injecting enough restraint to keep the song contained in its song walls rather than becoming a mere vehicle for his drumming. He created signature hooks, he made mediocre songs into good songs and good songs into great songs. He did all of this with a smooth, fluent and completely innate showmanship.

Watching Clem play the drums was almost a metaphysical thing—he was there in his own world, oblivious to you and simultaneously aware that he was performing. You might know nothing about him, who he was as a person, but watching him, even standing apart, at a distance, you were a part of his reality and existence. It was more than watching, it was intangible and formed of something fundamental and stripped away. It was bearing witness to the essence of a person, and it was hard to look away.

Two days after he died, I had the first Go-Go’s shows in a very long time where it was all five us. In 2022, we played a series of gigs with Clem subbing for Gina. He liked to say he was the best looking guy in the band. For Coachella, Audrey came out, which gave me more distraction. But returning alone to LA, the first of what I suspect will be many tidal waves of loss hit me. Yesterday, the grief was a hollow, ravaged hole and I was reduced to being just the edges around it.

Normally, we would have had long, involved discussions about the gigs, both the Roxy and Coachella. Normally, he wouldn’t have been at either of my shows because he would've been out of town, playing with one of the many bands he enjoyed playing with. Clem rarely stayed home. If he got off a months-long Blondie tour, he might be back for a week before leaving to play with another band, at a whole different level. I’ve emulated that ethic in many ways; being a working musician, not being a snob or thinking I was too successful or “above” a gig. I had a kid and pets and other interests and wasn’t in demand the way he was, but I’ve never stopped playing or being in bands and that’s because of him. It seemed like every gig I might get to play, he had already done, and he’d fill me in, whether it was a pub in Wales or a theater in Detroit or a festival like Coachella—the big one that I don’t get to discuss with him. It’s unimaginable to me that I will not be texting, video chatting and talking with him again.

Clem has done so many things that were important and kind and intended solely to support me and help me. I wish I’d made a list and made sure he knew I knew and recognized and appreciated each and every effort. I’m pretty sure I let him know at the time, but seen all together, it becomes a testament to what we meant to each other. In return, he knew from experience that I would drop everything and come to him when he needed me.

Me being in England is heartbreakingly Clem skewed; in many ways I’m living a chapter of my life that is a mirror of one he wanted and planned for himself. I’ve rented a house where he dreamed of living, I joined the gang at Chelsea Arts Club, where he hoped to belong, several of his friends I met from him are becoming my good friends. I recently loved a lunch at Soutine in St John’s Wood, and was told by my companion that it was one of Clem’s favorite places.

He is everywhere for me and always will be. I hope he knows that for so many of us, he will always be. Clem would have been astounded at the outpouring of love and respect and affection that flooded the press and media at his passing. He knew how good he was, he knew who his friends were, but I don’t think he knew how far and wide he’d made an impact. Equal or greater to the accolades about his talent was the repeated and continual collective praise of how he interacted with people; from talking with a drummer he’d just met at a gig while helping load their drums into the car to friendly chats while waiting in line next to a fan, to showing up and jamming with a local band. I read the accounts and stories for days and wasn’t surprised by any of it. He will be a featured character in my ongoing story, the future one I intend to write, the one I hope to live.

When I wrote “All I Ever Wanted” I wanted two things; for my book to be honest and real, and for it to be interesting and well written. I had no idea that Clem would emerge as one of the heroes of my book, but that was the outcome. Hundreds of people have told me that reading about him, and us, made his passing much more of a loss. It was already a magnitude loss, to have one of the best musicians in one of the most iconic and trailblazing bands of our generation die. It softens the harshness to think my story brought him into people’s hearts and minds in a more fully realized way than being a known or favorite musician did. I vow to continue, to the best of my ability, to make sure he is always remembered and known. Not just his legacy as a drummer, as a member of Blondie and other bands, but as a really good man and the best friend anyone could ever hope to have. I hope wherever he is, he is feeling good today.

This is such a beautiful tribute. I'm so sad I never got to meet him, but he was always one of my favorite musicians. Are you a person who mourns people before they die like I do? I hear familiar sounds in your words. The dream you mentioned is so important. Watch for upcoming dreams as he will likely come talk to you. All my love. And thank you for writing this. xo

How lucky that you found each other & you remained such wonderful companions over the decades! Lesser mortals would have lost all that after the romantic phase ended. Very fitting that this tribute is both drenched in love & loss as your relationship enters -once more- an entirely new phase. I have no doubt you’ll find Clem in music, in travel & in unexpected ways going forward.