Well Pleased

Birthday recap and some India

I was born at 4pm on a Wednesday on January 7th, the day Fidel Castro came to power in Cuba, in the year that one of my favorite all times records, Miles Davis “Kind of Blue” was released, also the year Buddy Holly died in a plane crash. Besides me, 1959 also brought Starburst candy, Barbie, and pantyhose into the world.

I don’t recall ever having a birthday party as a child, or having my mom make a big deal out of that day. But as an adult, I began to celebrate, and in the Go-Go’s I started a tradition where we had birthday dinners, which soon became exercises in trying to outdo each other in extravagance. This was made easier because it would all be paid on the band Amex card. These dinners are some of my favorite memories from our heyday, because not only would the whole band and inner circle attend, but a selection of friends would join. It was rare, really the only time, that we could socially integrate the outer life with the circus of an insulated band life.

Turns out I liked celebrating my birthday, and after we split up, I kept doing so, in far less high fashion, but enjoying bringing different branches of friendships together in one place. I’ve rarely let one go by without a bang.

After a pretty sad birthday last year in LA, with the Palisades and Alta Dena fires raging out of control, and Clem in his last living months, I wanted to try and reclaim the joy this year, in London. A couple weeks ago, I hosted my birthday celebration in the context of my new life, acquaintances and friends at the local pub.

Age-wise, to be closer to 70 than to 60 is weird, but I’ll take it, and I’ll also take the new-toy-times-exponential sensation of having managed to put together, day by day, text by text, call by call, effort by effort—the structure of a new life. It might not be the solid foundation, walls and roof that I had before, but it feels like shelter. I’m pretty damn pleased with myself. I’ve now collected enough people I’d like to share my birthday with to make it a social success. Every one had a blast and I’m happy I did it.

2026 has already given me another chance to be pleased with myself. I started writing this on the plane from London and want to real-time travelogue write again, something I did in the 90’s through Egypt and Turkey—this time about a couple of weeks of exploration in two countries. I won’t be alone the whole time, and I don’t think I’ll be doing any bribing of guards or other rogue tourist activities like that long ago Egypt trip, but it feels really good to be on an India adventure. (and beyond, which I’m holding out on til I get there.)

I’ve been in a car for a lot of driving, the Golden Triangle route that makes up Agra/Taj Mahal, Jaipur, and Delhi. I’m only in India for a week, it was a tag-on to another trip that launches out of Delhi. I figured if I was coming all the way to Delhi to meet a friend and fly elsewhere, I needed to find a reasonable itinerary and get where I could, at least get a taste and learn some interesting history. The Golden Triangle is absolutely do-able in a week, perhaps even less.

I don’t know how this country will stay with me. As a mature grown-ass woman, it’s the slow, steady, stay-lit candle that signals love more than the blowup of instant infatuation. So it doesn’t portend badly for India that the latter was not a part of my entry into it’s atmosphere. There’s inescapable chaos everywhere I’ve been, but there’s also discoverable quiet and meaningful connection, if one makes a point of looking beyond the surface.

Enough has been written about India to make it a challenge to wrap any original thoughts and words around the experience—but any self respecting writer’s gotta try.

The first thing I noticed about Delhi was the air quality, swathed in a haze of smog that made me feel dirty the moment I walked out of the airport. It’s a crisis for the city, and a concern for me, as I’ve had issues with my respiratory system in the past (mold induced) and I guard my lung health diligently. I went straight to a nearby hotel, checking in at 3am, and was glad to leave the next morning for a luxe hotel 600 meters from the Taj Mahal in Agra. For the next several days I reconsidered the plans for when I’d be returning to Delhi, deciding when I did, I’d skip some sightseeing and stay indoors as much as possible, and also get a mask for when I did venture out.

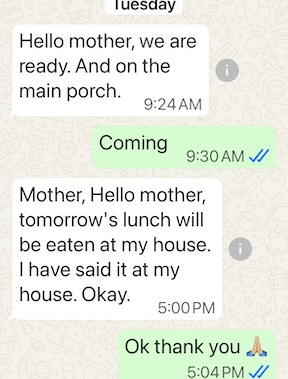

My driver, Mukesh, would be with me for the next four days. After sussing out my nature, something prompted him to inform me that he’d be calling me “mom” “Mother” or “maa.” It took questioning one of my guides to learn that this is meant to convey deep respect and protection—essentially letting me know he’d be looking after me and ensuring my safety—as much as he would for his own mother. I wanted to really play along and call him “son” but decided to let it be a one-sided thing—I didn’t want to cross any lines or alter the cultural context that afforded me mom stature. He stuck with it down the line; when I showed him a picture of Audrey, he said she was his sister. And after a few days, when I was invited to join Mukesh at his village home for a lunch with his family, he was quick to point out that his children were my grandchildren.

When Mukesh told me he was from the warrior caste, I was curious, isn’t that the one that’s up there, right below Brahmin? I did some research and learned that even though it is traditionally a highly ranked caste, many complex historical factors have led to Rajput warrior castes in rural and agricultural regions to be economically deprived. Since leaving Delhi, we’d driven through tons of villages down roads lined with countless ramshackle concrete abodes that looked unfinished or abandoned. I wondered if he lived somewhere like that.

I’d been asking about his family and his life. Any talk was done in very limited English, but somehow we’d manage. After telling me about his son and daughter, I was invited to stop at his home on the way from Jaipur to Delhi, 20 km out of the way. Of course. There was no way I’d turn down an invite to join Mukesh and his family and see what life is like for an average working and struggling Indian. He freelances as a driver for visitors, tourists and upscale travel companies, probably making a pittance of what they charge clients. And when tourist season is over, the work is over. He said he worries because he supports his whole family. His son was an engineering and electronic student and his daughter is a couple of years away from college too.

Being a driver in India is not like being a driver anywhere else. What could’ve been harrowing and stressful was neither in Mukesh’ car. He had snacks, drinks and pillows for me, and was excellent at inserting our vehicle into and out of the free-for-all riot that is traffic in India. Rickety buses crammed with bodies, hundreds of motorbikes, often with a guy driving, a sidesaddled sari’d woman on back and a kid or two in front, tuk tuks, and trucks painted in fading bright colors, festooned in garlands, glittery poms and tassles; cars and taxis, pedestrians, bicycles, cows, dogs. All of it is going somewhere, not in the same direction necessarily, and often without lanes, signs, signals, traffic cops, or any rules or laws that I could discern. Everything you’ve heard about the horns blaring is true. It’s not rudeness, it’s how to let someone know you’re there and you’re coming. Lots of trucks instruct approaching drivers to “blow horn.”

Everywhere, there is poverty, I expected this. Everywhere, there is humanity—I also expected this—India is the world’s most populated country, surpassing China in 2023, with something like 1.5 billion people. I think I’ve seen millions of them, doing nearly everything a person does in public; talking, gathering, leaning, standing. Napping on charpais outside in the shade, sat behind carts piled high with cashews or cauliflowers, green beans and apples. Farming, eating, squatting a full couple feet closer to the ground than I’ve ever gotten. Looking at phones, reading newspapers, herding goats, walking, urinating. (So far I’ve been spared the public poopers)

Row upon row of run down open faced markets, workplaces, shops, stores and services, enough stuff for 1.5 billion people to find what they need I guess. These are all funky as hell, but I actually think preferable to our hideous strip malls. Hardly anything looks finished. It’s like no one can be bothered to fix things up for the people, lets just make sure the tourists have enough normalcy to keep them coming back. Everything, and I mean everything else, looks to be in a state of derelict disrepair. There’s low walls, out of stone or concrete, painted in primary colored Hindu lettering, that just end in a pile of rubble, partial fences, tin gates, haphazard tire piles and smoldering fires. Over and over I see what looks like a pile of rocks, excavated for a structure foundation maybe, that’s just been left there after the digging, with nothing ever built.

But it’s all populated. Red or brown plastic chairs arranged outside all of these places, with men talking and smoking. I’m trying to imagine what they talk about. Women walk alone or in small groups, wrapped in colorful, sparkly fabrics, or sit in front of these bunker-like concrete boxes, strewn with debris and piles of junk like it’s any yard or patio of any house. Chickens, dogs, and of course, cows, goats wander everywhere.

Everything but cats. I haven’t seen one cat. I asked Mukesh and his son about that when I’m at their house, they look very uncomfortable, shaking their head, no, no. I do a short research jag on India’s catphobia dislike and decide right there and then it’s a big strike in the cons column.

It turns out Mukesh and his family do live in one of the concrete boxes. He apologized for it being “unfinished.” As we pull up, he said, “I am not rich. My house is small.” Before, he’d warned me, but reassured me that even though his house was small, his heart was big. Like mine.

There was block-printed Indian fabric hanging outside, bringing some color to the entry. The front door entered into a room with a made bed, and a brown plastic chair. His son, smiling his blinding white teeth at me, ran to get two more chairs and a small square table. I was instructed to sit, and had little bouts of talk with the son punctuated by silences and smiles. A couple of small pictures hung, too high, on the concrete walls. No rug on the concrete floor. I could hear his wife cooking in the next room. After the food was brought out, all on a metal platter, I was instructed to eat.

“How?” I asked him. I didn’t see a plate, just the platter, and some bowls of dahl, spinach aloo, and biryani.

He began spooning on to the platter which apparently was actually a plate. I was given a spoon and ate while he watched me carefully.

“Better than the Oberoi” I told him. That seemed to please him. The son brought another platter/plate, and Mukesh began to eat too.

His wife was the last to join us. She’d gotten dressed up for the occasion, in a beautiful red and gold sari. We all smiled a lot and Mukesh looked worried whether I was enjoying myself. I was. We showed each other photos, and I decided to see what would happen if I showed them a photo of me onstage playing. They all didn’t know what to make of it. I was told the daughter, still at school, liked music. “Everyone likes music” I said. A neighbor came to look at/meet me.

I asked how many rooms, and was given a tour. There was a large kitchen area and two other bedrooms. One had the Hindu shrine, with all the gods and goddesses. Hindus can pick which ones they want to focus their worship on, I guess Mukesh couldn’t decide, or wants to cover all the bets. I asked him and his son to show me what to do in front of the shrine, so we all sat cross-legged, put our hands together, and meditated and thought and asked the Gods whatever each of us was wanting bestowed. I told them a bit later that I thought Sarasvati had been good to me, which went over really well. Sarasvati is the Hindu goddess of arts, music, intelligence and wisdom.

It was altogether an awkwardly wonderful time. I don’t think any other person Mukesh has driven has been invited to his village for lunch with his family. I have a feeling the village will be talking about it for years. I am well pleased with myself for going.

If you enjoy my writing please subscribe, it really helps! Thank you so much, more to come. xxK

What a wonderful retelling of your experience. You made him and his family happy by accepting his invitation and created a memory for them that will stay with them always. Human connection and an opening of hearts through it. That’s what travel, and life, is about.

Happy belated birthday! I'm a couple of years behind you (you're my brother's age 😀), and when I hit my big milestone last year, I, too, decided to start saying yes to things where, in the past, I've always thought, no, how could I? It has made my days so much richer.

And it's clear that with all the challenges on your emotional and even just logistical plate, you are saying yes, too! This trip sounds like a great big leap into an unfamiliar world, and you stuck the landing--with grace, humility, but also with perspective. Thanks for sharing it all.

Wishing lots more yesses in your new year that bring you joy.